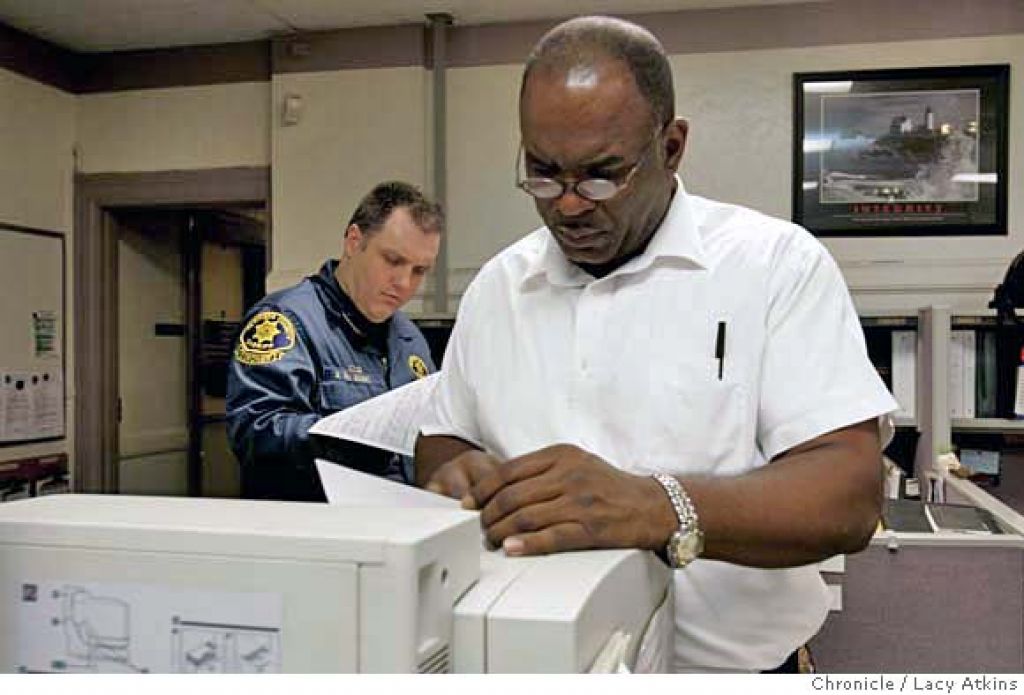

Charles Brewer - Oakland Deputy Coroner

Images by Lacy Atkins

Despite rappers who chant odes to their guns and movies that feature choreographed car wrecks and shootouts, these investigators know firsthand that there is nothing glamorous about a body riddled with bullets or mangled in a crash.

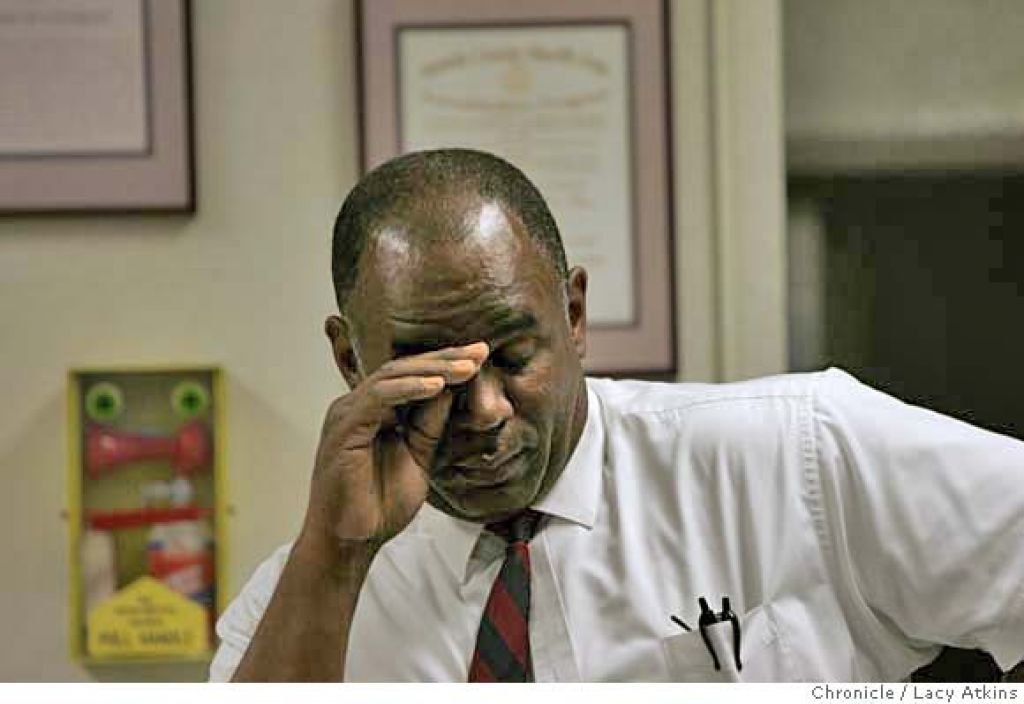

But to Brewer, the hard part is not the corpses. It’s looking unsuspecting family members in the eyes and telling them that a loved one has died.

“After a few weeks, you get used to the bodies, but notifications are always difficult,” said Brewer, 50, a coroner’s investigator since 1999. “Here I am, a stranger, coming to your door in the middle of the night to bring you some very bad news. It’s incredibly stressful, and you never know how people are going to handle it.”

Because the reaction from family members can be so unpredictable, investigators always make notifications in pairs. If the family is local, they try to contact relatives in person. If the family member is alone, the investigators will hang around until another relative or friend arrives.

People’s reactions range from shouting insults at the investigators to collapsing in their arms. McAdams had a distraught father swing at him. Brewer has endured death threats. They also have been offered coffee by loved ones struggling to retain some composure after receiving the traumatic news. And they have seen parents nod their heads, as if the violent death of an adult son or daughter were no surprise.

“Occasionally, you see someone who reacts as if they expected this sooner or later,” said McAdams, 40, an investigator for nine years. “They are hurt. They are upset. But they are not really surprised.”

Notifications are one of the more vexing aspects of a complicated and often thankless profession — one that has little similarity to the popular “CSI” television shows. The coroner’s duty is to investigate, document and explain unnatural death.

Investigators like Brewer and McAdams are the key link between police and paramedics on the street and the forensic pathologists who perform autopsies nearly every weekday at the coroner’s lab in a nondescript building near Jack London Square.

“We are not focused on who did it,” Brewer said. “That’s for the police. We focus on how he did it. How did this guy die?”

The coroner’s office handles about 3,800 death cases each year. Of those, about 1,100 involve a coroner’s autopsy.

The rest are so-called memorandum cases, or deaths by natural causes or contagious illnesses, such as AIDS or hepatitis, that are researched and documented by investigators but do not require an autopsy to establish the cause of death. The investigators are known for their role in helping to solve crimes, but they are also front-line data collectors for public health agencies and academics who study death.

Virtually all violent or suspicious deaths require an autopsy and a detailed investigation that often starts at the crime scene.

Read the Full Article of Oakland: A Plague of Killing